Predictors of Poor Participation in Mammographic Breast Cancer Screening among Women in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria

AN Mbaba, MP Ogolodom, N Alazigha, R Abam, BU Maduka, ID Jaja, DC Ugwuanyi, VK Nwodo, and AC Okwor

AN Mbaba1, MP Ogolodom2*, N Alazigha1, R Abam1, BU Maduka3, ID Jaja4, DC Ugwuanyi5, VK Nwodo5, and AC Okwor6

1Department of Radiology, Rivers State University Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt Rivers State, Nigeria

2X-ray Department, Zonal Hospital Ahoada, Rivers State, Nigeria

3Department of Medical Radiography and Radiological Sciences, University of Nigeria Enugu Campus, Nigeria

4Department of Community Medicine, Rivers State University, Nkpolu-Oroworukwo, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

5Department of Radiography and Radiological Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Nnewi Campus, Awka Anambra State, Nigeria

6Department of Radiology, Alex Ekwueme Federal University Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki, Ebony State, Nigeria

- Corresponding Author:

- MP Ogolodom

Department of X-ray, Zonal Hospital Ahoada

Rivers State, Nigeria

E-mail: mpos2007@yahoo.com

Received: March 15, 2021; Accepted: March 30, 2021; Published: April 08, 2021

Citation:Mbaba AN, Ogolodom MP, Alazigha N, Abam R, Maduka BU, et al. (2021) Predictors of Poor Participation in Mammographic Breast Cancer Screening among Women in Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria. Crit Care Obst Gyne Vol.7 No.3:28.

Abstract

Morbidity and mortality from breast cancer can be reduced if detected early and breast cancer screening is the ultimate strategy for early diagnosis. Understanding the determinants that influence patient’s failure to embrace or participate in preventive care is a prerequisite for strategies to reverse the trend.

Objective: This study was designed to identify the predictors of poor participation in mammographic breast cancer screening in our setting to encourage women to adopt preventive health care measures.

Material and Methods: This was a questionnaire-based descriptive study whose validity was calculated using the Index of item Objective Congruence (IOC). Questionnaire administration and retrieval of responses were physically and electronically done. The entire study lasted for two months (July to August 2020).

Results: Two hundred completed questionnaires were retrieved and analyzed. The mean age of the participants was 39.3 ± 14.6 years. A larger number 60.5% (n=121) of the participants had tertiary education. With regards to the level of the participants’ awareness of breast cancer, a large proportion of 91.5% (n=183) has heard of breast cancer. The majority 67.7% (n=135) of the participants had no family history of breast cancer. A greater number 87.5% (n=175) of the participants have heard of mammography as a breast cancer screening method. Most 41.5% (n=83) of the participants have not undergone mammography examination because none was in their vicinity, followed by those that we're afraid of radiation 28.5% (n=57) and the least 19% (n=18) attributed their reason of not going for mammography to the attitude of the attendants.

Conclusion: In a resource-constrained setting, factors such as education, household income, availability, and affordability of breast cancer screening services are important predictors of participation in breast cancer screening exercises as documented in this study.

Keywords

Breast cancer; Participation; Predictors; Screening

Introduction

Breast cancer is a major malignancy found in women, accounting for 19% of all cancers and the second most common cause of death among them globally [1,2]. In 2015, about 2.4 million new cases of breast cancer were diagnosed and 523,000 deaths were documented worldwide [3]. There is a steady rise in the incidence of breast cancer in sub-Saharan African [4], and in Nigeria, evidence from two cancer registries demonstrate that the incidence rate of female breast cancer per 100,000 has increased from 24.7% in 1999 to 54.3% in 2012 [5,6]. The peak age of breast cancer in Nigerian women is about a decade earlier than that of Caucasians [7,8] and some cases have even been reported among women aged below 30 years [9]. Breast cancer patients, in Africa, often present with advanced stages of the disease than their western counterparts with a concomitant increase in mortality rate [10]. In Nigeria, about 70% of these patients present late when no known remedy can reverse disease progression.

Evidence has shown that morbidity and mortality from breast cancer can be reduced if detected early and breast cancer screening is the ultimate strategy for early diagnosis [11,12]. The established methods of breast cancer screening include Breast Self-Examination (BSE), clinical breast examination, and mammography each with its advantages and disadvantages [13]. In developed countries, more than 50 percent of eligible women participate in breast screening [14]. In developing countries, there is poor knowledge of breast cancer screening among women and consequently, do not engage in the screening practices. Factors militating against breast cancer screening practices according to some studies include inadequate knowledge or awareness of screening services, family income, culture, and levels of education of participants [15,16].

Screening mammography has not gained popularity in Nigeria [17-19], and the incidence of breast cancer is rising in our environment, necessitating the need for early detection as this would increase the treatment options available to affected women and improve outcomes [20]. A study in Nigeria, documented the value of screening mammography even in asymptomatic women with a call on the women to engage in breast screening practices [21]. The decline in breast cancer deaths in Western climes in recent times has been attributed partly to early presentation and diagnosis through breast cancer screening services [22]. It is common knowledge that preventive care measures have effectively reduced morbidity and mortality from breast cancer and understanding the determinants that influence patient’s failure to embrace or participate in preventive health care services are prerequisites for strategies to reverse the trend [23]. It is possible that the women of this region may have different trends and health-seeking behavioral patterns when compared to the general women population of this country. In this study, we aimed to identify the predictors of poor participation of mammographic breast cancer screening in our setting to encourage our women to adopt preventive health care, particularly as regards breast cancer screening.

Methods

This was a questionnaire-based descriptive study carried out among women in Port Harcourt Metropolis, Rivers State, South- South, Nigeria. The questionnaire used in this study was designed by the authors, While the validity of the questionnaire was calculated using the index of Item Objective Congruence (IOC) as used by previous researchers [24,25].The content validity of the questionnaire was determined by calculating the index of Item Objective Congruence (IOC). According to the index parameters, an IOC score >0.6 was assumed to show good content validity. All the scores obtained in this study for all the items of the questionnaire after IOC interpretation were >0.6.

The questionnaire consisted of two sections. The first section was made up of three questions on the participants’ sociodemographic variables such as age, educational status, and occupation. The second section, which consisted of 15 questions, evaluated the participants’ awareness of breast cancer, breast cancer screening methods, determinants of partaking in breast cancer screening, and the ways to encourage women to embrace breast cancer screening. We employed both paper and online versions of the questionnaire in this study. The online version, which was designed using Enketo Express for Kobo Toolbox, was used to obtain information from the participants with whom we could not come in contact. The link of the online version of the questionnaire was distributed to the participants through email addresses and WhatsApp platforms where they had access to fill the questionnaire, while the paper version was administered to the participants using one on one method. The completed paper questionnaires were manually retrieved immediately while the responses from the online version were retrieved electronically. The entire study lasted for two months (July to August 2020).

The aim of the study was clearly stated in the questionnaire and the participant’s consents were properly sought before they were recruited into the study. All participants’ information was treated with a high level of confidentiality. The participants were instructed to fill the questionnaire just once to avoid duplication of data and their participation in this study was voluntary. Data generated in this study were collected using a data spreadsheet and processed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. The processed data were analyzed using descriptive statistics such as table, mean, standard deviations, and bar chart.

Results

Two hundred completed questionnaires were retrieved and analyzed. The mean age of the participants was 39.3 ± 14.6 years with the majority 41.5% (n=83) within the age group of 41-50 years old. A larger number 60.5% (n=121) of the participants had tertiary education and the least 2% (n=4) had no formal education. A good number 42% (n=84) of the participants were civil servants, followed by professionals 36.5% (n=73). Among the professionals, nurses were highest in number 10% (n=20), followed by doctors 9% (n=18) and the least 3.5% (n=7) were radiographers (Table 1).

| S/N | VARIABLE | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| a) | Age group | ||

| <20 years | 8 | 4.0 | |

| 20-30 years | 18 | 9.0 | |

| 31 - 40 years | 37 | 18.5 | |

| 41- 50 years | 83 | 41.5 | |

| 51 years and above | 54 | 27.0 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| b) | Educational Status | ||

| Primary | 19 | 9.5 | |

| Secondary | 56 | 28 | |

| Tertiary | 121 | 60.5 | |

| None | 4 | 2.0 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| c) | Occupation | ||

| Artisan | 10 | 5.0 | |

| Petty Tractors | 33 | 16.5 | |

| Civil Servant | 84 | 42.0 | |

| Professional | 73 | ||

| Accountant | 2 | 1.0 | |

| Primary Health care workers | 16 | 8.0 | |

| Nurses | 20 | 10 | |

| Radiographers | 7 | 3.5 | |

| Doctors | 18 | 9 | |

| Teachers | 10 | 5 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

TABLE 1: Socio-demographic variables of the participants.

With regards to the level of the participants’ awareness of breast cancer, a large proportion of 91.5% (n=183) have heard of breast cancer. The majority 67.7% (n=135) of the participants had no family history of breast cancer and the least 6% (n=12) had a family history of breast cancer. Most of the participants 81.5% (n=163) perceived breast cancer as a deadly disease that can be treated if detected early and 11.5% (n=23) of the participants had no idea about what breast cancer was (Table 2).

| S/N | QUESTIONS | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) | Have you heard of breast cancer? | ||

| Yes | 183 | 91.5 | |

| No | 17 | 8.5 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| 2) | Is there any history of breast cancer in your family | ||

| Yes | 12 | 6.0 | |

| No | 135 | 67.5 | |

| Don’t know | 53 | 26.5 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| 3) | What do you know about breast cancer? | ||

| Simple disease like malaria | 0 | - | |

| A deadly disease that can be treated if detected early | 163 | 81.5 | |

| A deadly disease that cannot be treated | 14 | 7.0 | |

| A disease caused by witchcraft | 0 | - | |

| Don’t know anything about the disease | 23 | 11.5 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

Table 2: Frequency and percentage distribution of participant’s level of awareness of breast cancer.

The result of the participant’s awareness level of breast cancer screening revealed that out of 200 participants 86.5% (n=173) were aware of breast cancer screening. The majority 54% (n=128) of the participants knew about Self Breast Examination (SBE) as a breast cancer screening method, followed by those that know about mammography 23.5% (n=47). A large number 83.5% (n=167) of the participants practice at least one of the methods of breast cancer screening (Table 3).Out of 33 participants that do not practice any of the breast cancer screening method, 30.3% (n=10) perceived fear of results as their reasons, followed by those that don’t know where to go for the screening 24.25% (n=8) and the least were religious belief and culture, which is 6.06% (n=2) each (Table 3). A greater number 87.5% (n=175) of the participants had heard of mammography as a breast cancer screening method. Most 41.5% (n=83) of the participants, did not go for mammography examination because none was in their vicinity, followed by those that we're afraid of radiation 28.5% (n=57) and the least 19% (n=18) attributed their reason of not going for mammography to the attitude of the attendants. Out of 200 participants, 68.5% (n=137) practiced Self breast examination. Among those that do not practice Self-breast examination, majority 61.9% (n=39) of the participants don’t know how to do it (Table 3).

| S/N | QUESTIONS | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Are you aware of breast cancer screening | ||

| Yes | 173 | 86.5 | |

| No | 27 | 13.5 | |

| Total | 100 | ||

| 2 | Which methods of breast cancer screening do you know? | ||

| Self-examination | 108 | 54 | |

| Clinical breast examination | 27 | 13.5 | |

| Mammography | 47 | 23.5 | |

| All methods | 18 | 9.0 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| 3) | Are you practicing any of the methods? | ||

| Yes | 167 | 83.5 | |

| No | 33 | 16.5 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| 4) | If No to question 3 above, what are you reasons? | ||

| Household income | 64 | 12.12 | |

| Salary not enough and can’t afford the cost of the test | 17 | 21.21 | |

| Fear of results | 10 | 30.30 | |

| Culture | 2 | 6.06 | |

| Religious Belief | 2 | 6.06 | |

| Don’t know where to go | 6 | 24.25 | |

| Not interested | |||

| Total | 33 | 100 | |

| 5) | Have you heard of mammography as a method of breast cancer screening? | ||

| Yes | 175 | 87.5 | |

| No | 25 | 12.5 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| 6) | What will make you not to go for mammography? | ||

| Fear of radiation | 57 | 28.5 | |

| Not in your varianity | 83 | 41.5 | |

| Fear of pain of compression | 22 | 11.0 | |

| Attitude of the attendants | 18 | 9.0 | |

| The cost of the test | 20 | 10 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| 7) | Breast self-examination does not attract any cost, do you practice it? | ||

| Yes | 137 | 68.5 | |

| No | 63 | 31.5 | |

| Total | 200 | 100 | |

| 8) | If no to question 9 above, what are you reasons? | ||

| Don’t know how to do it | 39 | 61.90 | |

| Know how to do it but don’t like doing it | 24 | 38.1 | |

| Total | 63 | 100 | |

Table 3: Participant’s awareness level of breast cancer screening.

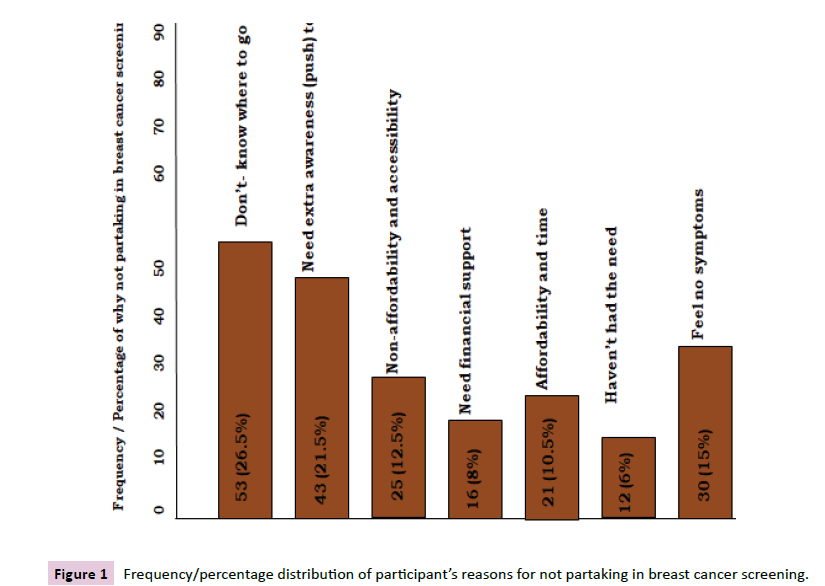

Greater number 26.5% (n=53) of the participants don’t know where to go for breast cancer screening followed by those that said that there is a need to create more awareness on breast cancer screening 21.5% (n=43) and the least 6% (n=12) said that they did not need breast cancer screening (Figure 1).

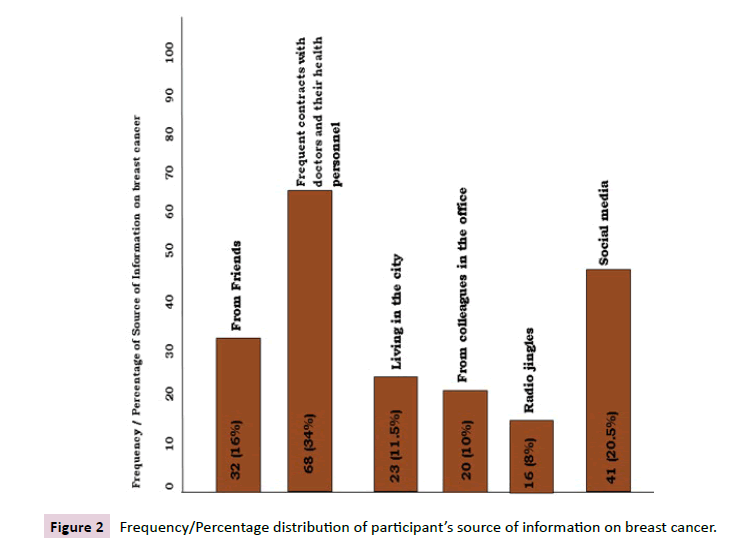

A good number 34% (n=68) got information on breast cancer due to their frequent contacts with doctors and other health personnel, followed by those that got information from social media 20.5% (n=41) and the least 8% (n=16) got information from radio jingles (Figure 2).

Participants’ suggestions on how to encourage them to embrace breast cancer screening were evaluated and the results revealed that out of 200 participants, 57% (n=102) agreed that breast cancer screening should be free, followed by those that strongly agreed 29% (n=58) and the least strongly disagreed 6% (n=12). The majority 57% (n=114) agreed that more screening centers should be established. Most of the participants 59.5% (n=119) strongly agreed that effort should be made at increasing awareness (Table 4).

| S/N | QUESTIONS | FREQUENCY | PERCENTAGE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1) | What do you think should done to encourage women to embrace breast cancer screening | ||

| A) | It should be free | - | - |

| a. | Strongly disagree | 12 | 6% |

| b. | Disagree | 13 | 6.5% |

| c. | Somewhat disagree | 15 | 7.5% |

| d. | Agree | 102 | 51% |

| e. | Strongly agree | 58 | 29% |

| Total | 200 | 100% | |

| B) | More screening centres should be established | ||

| a. | Strongly disagree | 1 | 0.5% |

| b. | Disagree | 0 | 0% |

| c. | Somewhat disagree | 3 | 1.5% |

| d. | Agree | 114 | 57% |

| e. | Strongly agree | 82 | 41% |

| Total | 200 | 100% | |

| C) | Effort should be made at increasing awareness | ||

| a. | Strongly disagree | 3 | 1.5% |

| b. | Disagree | 0 | 0% |

| c. | Somewhat disagree | 2 | 1.0% |

| d. | Agree | 76 | 38% |

| e. | Strongly agree | 119 | 59.5% |

| Total | 200 | 100% | |

Table 4: Participant’s suggestions on how to encourage them to embrace a breast cancer screening.

Discussion

The findings of this study revealed that the majority of the participants were within the 4th, 5th decades, and above with the highest number in the age range of 41-50 years. This finding is inconsistent with the findings of the studies conducted by [1, 18, 22, 26-29]. The differences in our findings could be attributed to the sample sizes used in the various studies.

More than 60% of the participants, which was the highest percentage in this study had tertiary educational status. This finding is in agreement with the findings of the studies conducted by [1,18,22,29]. Contrary to our findings on the participants' educational status, Oladimeji et al. [28], reported participants with secondary educational status to be highest. The discrepancies in our findings could be ascribed to the differences in our sample sizes.

With regards to the participants’ awareness level of breast cancer, our study revealed a high level of awareness of breast cancer among our study participants with more than 91% rating. This finding is consistent with the findings of similar studies conducted by [29-35]. In contrast to our finding, Okobia et al. [22], reported poor knowledge of participants about breast cancer. The level of awareness about breast cancer varied among the population of the different studies as they documented different absolute values of the level of awareness. The high levels of breast cancer awareness noted in our study could be ascribed to the number of participants with higher educational status.

A greater number of participants in our study got the information on breast cancer due to their contacts with doctors and other health personnel. This finding is in keeping with the findings of previous studies conducted by Eguvbe [32] and Omotara et al. [36]. In contrast to our findings, other authors reported different sources of information on breast cancer in their studies. Salaudeen et al. [37] and Bello et al. [30], reported television, Irurhe [38], reported textbooks, Omotara et al. [36], reported friends. The sources of information about breast cancer differ among the population and the differences could be ascribed to the difference in the sample sizes used in the various studies and the geographical variations of the aforementioned studies.

This study revealed that most of the participants had no family history of breast cancer. This finding is similar to the finding of the study carried out by Amoran and Toyobo [1] in Nigeria among women of reproductive age group in a rural town.

Over 80% of the participants in this study perceived breast cancer as a deadly disease that can be treated if detected early. This finding is in keeping with the finding of the research work done by Younis et al. [29]. In contrast, was the finding of the study conducted by Okobia et al. [22], in which a greater number of their participants perceived breast cancer to be non-curable even when detected early. The identified discrepancies in our findings could be ascribed to a difference in the sample sizes, nature of studies, and geographical locations of the studies.

Approximately 87% of the participants in this study were aware of breast cancer screening with a majority having a good knowledge of BSE. Our finding is similar to the findings of the studies carried out by Amoran and Toyobo [1] and Foluso and Noela [27] all in southwestern Nigeria.

With regards to the participants’ practice of any breast cancer screening method, the majority of the participants in our study carried out any form of breast cancer screening. This finding is in agreement with the findings of the studies conducted by Kordan-Souraki et al. [26] in the Northern part of Iran. However, studies conducted by Oladimeji et al. [28], in Ibadan, Oyo State, Western Nigeria, Amoran and Toyobo [1] in Ogun State, Western Nigeria, Ojewusi et al. [39], Balogun and Owoaje [40], among market women, were inconsistent with the results of this study. The discrepancies in our findings could be attributed to the various study population, sample sizes, and geographical variation among the participants who did not practice any of the methods of breast cancer screening, the majority attributed their reasons to fear of results, followed by those that don’t know where to go for the screening. Other reasons, which were also stated include need extra-awareness, non-affordability and accessibility, need financial support, time, haven’t had the need, and feel no symptoms. The reasons for participants not practicing any method of breast cancer screening varied among various studies, but the common ones were lack of knowledge on how to perform breast self-examination [1,28], fear of finding a lump [31,41], no symptoms [35,36], lack of awareness [22]. Others felt they were violating their bodies by palpating their breasts [35,41,42] not considering it necessary [35,41]. The variations in our participants' reasons for not participating in any breast cancer screening technique could be ascribed to the different populations studied.

The greater population of the participants in our study was aware of mammography as a breast cancer screening method. This finding is consistent with the findings of previous studies conducted by Akhigbe and Omuemu [43] and Ojewusi et al. [39]. Most of the participants that have heard of mammography did not go for mammography examination because none was found in their vicinity, fear of radiation, household income, fear of the result, an attitude of the attendants, and cost of the test. Similar studies were conducted by Obajimi et al. [18] Younis et al. [29], Kardan-Souraki et al.[26]Younis et al. [29] reported a lack of time and that their participants did not believe they were at risk. The participants knew there was a risk in undergoing mammography investigation Obajimi et al. [18] and household income was related to breast cancer screening Kardan-Souraki et al. [26]. The reported reasons vary depending on the nature of the studies and the geographical locations. According to Kardan-Souraki et al. [26] study conducted in Iran, women with high household incomes had a high rate of screening. Due to the aforementioned reasons and its implications on the practice of mammography breast cancer screening, the Korean government provides free screening services to low-income people [44]. Creating more awareness on mammography screening techniques and the Nigerian government making the mammography screening services free in our locality will increase the rate of mammography breast cancer screening which will invariably reduce the rate of breast cancer morbidity and mortality.

A large number of the participants agreed that making mammography investigation free will encourage more women to be actively involved in breast cancer screening exercises. This finding is in line with the ideology of the Korean government, in which breast cancer screening was made free especially for low-income people [44]. The establishment of several breast cancer screening centers will enable more women to partake in mammography investigation.

Conclusion

In a resource-constrained setting, factors such as education, household income, availability, and affordability of breast cancer screening services are important predictors of participation in mammographic breast cancer screening as documented in this study. Breast cancer screening campaigns aimed at bridging the knowledge gaps in breast cancer awareness should be promoted among the general population, especially among illiterate women and those with lower education. There is a need for the establishment of more breast cancer screening centers as well as designing and implementing organized breast cancer screening programs.

Funding/Conflicts of Interests

We report no funding assistance or conflicts of interest.

References

- Amoran OE, Toyobo OO (2015) Predictors of breast self-examination as cancer prevention practice among women of reproductive age-group in a rural town in Nigeria. J Niger Med 56: 185.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A (2016) Cancer statistics. Cancer J Clin 66: 7-30.

- Fitzmaurice C, Allen C, Barber RM, Barregard L, Bhutta ZA et al. (2017) Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol 3: 524-548.

- Forouzanfar MH, Foreman KJ, Delossantos AM, Lozano, Lopez AD et al. (2011) Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: a systematic analysis. The lancet 378: 1461-1484.

- Parkin DM, Ferlay J, Sitas F, Thomas JO, Wabinga H et al. (2003) Cancer In Africa. IARC.

- .

- Jedy-Agba E, Curado MP, Ogunbiyi O, Fabowale T, Igbinoba F et al. (2012) Cancer incidence in Nigeria: a report from population-based cancer registries. J Cancer Epidemiol 36: 271-278.

- Okobia MN, Osime U (2001). Clinicopathological study of carcinoma of the breast in Benin City. Afr J Reprod Health 5: 56-62.

- Banjo AAF (2004) Overview of breast and cervical cancers in Nigeria: are there regional variations In Paper presentation at the International workshop on new trends in Management of breast and cervical cancers, Lagos, Nigeria 1-12.

- Anyanwu SN (2000) Breast cancer in eastern Nigeria: a ten year review. West Afr J Med 19, 120-125.

- Gakwaya A, Kigula-Mugambe JB, Kavuma A, Luwaga A, Fualal J et al. (2008). Cancer of the breast: 5-year survival in a tertiary hospital in Uganda. Br J Cancer 99: 63-67.

- Bozorgi N, Khani S, Elyasi F, Moosazadeh M, Janbabaei G et al. (2018) A Review of Strategies to Promote Breast Cancer Screening Behaviors in Women. J Mazandaran Univ Med Sci 28: 243-255.

- Shetty MK (2010) Screening for breast cancer with mammography: current status and an overview. Indian J Surg Oncol 1: 218-223.

- Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Eyre HJ (2005) American Cancer Society Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer 2005. CA Cancer J Clin 55: 31-44.

- Vahabi M, Lofters A, Kumar M, Glazier RH (2015) Breast cancer screening disparities among urban immigrants: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health 15: 1-12.

- Ojewole F , Muoneke N (2017) Factors Predicting the Utilization of Breast Cancer Screening Services among Women Working in a Private University in Ogun State, Nigeria. AJMAH 2017 8: 1-9.

- Khaliq W, Aamar A, Wright SM (2015) Predictors of non-adherence to breast cancer screening among hospitalized women. PloS One 10: 26-32.

- Akinola R, Wright K, sunfidiya O, Orogbemi O, Akinola O (2011) Mammography and mammographic screening: are female patients at a teaching hospital in Lagos, Nigeria, aware of these procedures. Diagn Interv Radiol 17: 125-129

- Obajimi MO, Ajayi IO, Oluwasola AO, Adedokun BO, Adeniji-Sofoluwe AT et al. (2013) Level of awareness of mammography among women attending outpatient clinics in a teaching hospital in Ibadan, South-West Nigeria. BMC public health 13: 1-7.

- Olugbenga-Bello A, Oladele EA, Bello TO, Ojo JO, Oguntola AS (2011) Awareness and breast cancer risk factors: perception and screening practices among females in a tertiary institution in Southwest Nigeria. Niger Postgrad Med J 18: 8-15.

- Mbaba AN, Ogolodom MP, Ijeruh OY, Alazigha N, Abam R et al. (2020) Breast Imaging Findings among Asymptomatic Women who Underwent Screening Mammographic Examination in Port Harcourt, South-South, Nigeria 8: AJBSR.MS.ID.001322.

- Okobia MN, Bunker CH, Okonofua FE, Osime U (2006) Knowledge, attitude and practice of Nigerian women towards breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. World J Surg Oncol 4: 1-9.

- Faronbi JO, Abolade J (2012) Self Breast Examination practices among female secondary school teachers in a rural community in Oyo State, Nigeria. Open Journal of Nursing 2: 111-115.

- Okobia MN, Bunker CH, Okonofua FE, Osime U (2006) Knowledge, attitude and practice of Nigerian women towards breast cancer: a cross-sectional study. World J Surg Oncol 4: 1-9.

- Peto R, Boreham J, Clarke M, Davies C, Beral V (2000) UK and USA breast cancer deaths down 25% in year 2000 at ages 20-69 years. Lance 355: 1822.

- Turner RC, Carlson L (2003) Indexes of item-objective congruence for multidimensional items. Int J Test 3: 163-171.

- Ogolodom MP, Mbaba AN, Alazigha N, Erondu OF, Egbe NO et al. (2020) Knowledge, attitudes and fears of healthCare workers towards the corona virus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in South-South, Nigeria. Health Sci J, 1: 1-10.

- Ibrahim OM, Gabre AA, Sallam SF, El-Alameey IR, Sabry RN et al. (2017) Influence of interleukin-6 (174G/C) gene polymorphism on obesity in Egyptian children. Open Access Maced J Med Sci, 5: 831.

- Foluso O, Noela M (2017) Factors Predicting the Utilization of Breast Cancer Screening Services among Women Working in a Private University in Ogun State, Nigeria. AJMAH, 8: 1-9.

- Oladimeji KE, Tsoka-Gwegweni JM, Igbodekwe FC, Twomey M, Akolo C et al. (2015) Knowledge and beliefs of breast self-examination and breast cancer among market women in Ibadan, South West, Nigeria. PloS One, 10: e0140904.

- Younis M, Al-Rubaye D, Haddad H, Hammad A, Hijazi M (2016) Knowledge and Awareness of Breast Cancer among Young Women in the United Arab Emirates. Adv Breast Cancer Res 5: 163-176.

- Eguvbe AO, Akpede N, Arua NE (2014) Knowledge of Breast Cancer and Need for its Screening Among Female Healthcare Workers in Oshimili South Local Government Council Area of Delta State, Nigeria. Afri medic J 5: 59-64.

- Obaji N, Elom H, Agwu U, Nwigwe C, Ezeonu P, et al. (2013) Awareness and practice of breast self-examination among market women in Abakaliki, South East Nigeria. Ann. Med. Health Sci. Res. 3: 7-12.

- Agwu UM, Ajaero EP, Ezenwelu CN, Agbo CJ, Ejikeme BN (2007) Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self-examination among nurses in Ebonyi State University Teaching Hospital, Abakaliki. Ebonyi Med J 6: 447.

- Bello TO, Olugbenga-Bello AI, Ogunsola AS, Adeoti ML, Ojemakinde OM (2011) Knowledge and practice of breast cancer screening among female nurses and lay women in Osogbo, Nigeria. West Afr J Med 30: 296-300.

- Isara AR, Ojedokun CI (2011) Knowledge of breast cancer and practice of breast self-examination among female senior secondary school students in Abuja, Nigeria. J Prev Med Hyg 52: 186-190.

- Salaudeen AG, Akande TM, Musa Ol (2009) Knowledge and Attitudes to Breast Cancer and Breast Self-Examination among Female Undergraduates in a State in Nigeria. Eur J Soc Sci 3: 157-165.

- Irurhe NK, Raji SB, Olowoyeye OA, Adeyomoye AO, Arogundade RA et al. (2012) Knowledge and Awareness of Breast Cancer among Female Secondary School Students in Nigeria. Acad. J Cancer Res 5: 1-5.

- Bassey RB, Irurhe NK, Olowoyeye MA, Adeyomoye AA, Onajole AT (2011) Knowledge, attitude and practice of breast self-examination among nursing students in Lagos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria. Educ Res 2: 1232-1236.

- Omotara B, Yahya S, Amodu M, Bimba J (2012) Awareness, attitude and Practice of Rural women regarding Breast Cancer in Northeast Nigeria. J Commun. Med Health Educ 2: 148.

- Aniebue PN, Aniebue UU (2008) Awareness of breast cancer and breast self-examination among female secondary school teachers in Enugu metropolis, south-eastern Nigeria. Int J Med Health Dev 13: 105-110.

- Gali BM (2013) Breast cancer awareness and screening practices among female health workers of university of Maiduguri teaching hospital BOMJ 10.

- Akhigbe AO, Omuemu VO (2009) Knowledge, attitude and practices of breast cancer screening among female health workers in a Nigerian Urban City. BMC Cancer 9: 203-206.

- Lee K, Lim HT, Park SM (2010) Factors associated with use of breast cancer screening services by women aged =40 years in Korea: The Third Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005 (KNHANES III). BMC cancer, 10: 1-11.

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences