Factors Associated with Men's Participation in Postpartum Family Planning: A Study of Kiswa Health Centre III, Kampala, Uganda

Omona Kizito*and Mahoro Rose Mary

Department of Communication and Policy, Uganda Martyrs University, Kampala, Uganda

- *Corresponding Author:

- Omona Kizito

Department of Communication and Policy,

Uganda Martyrs University, Kampala,

Uganda,

Tel: 0706464873;

E-mail: kizitoomona@gmail.com

Received date: April 09, 2022, Manuscript No. IPCCO-22-13066; Editor assigned date: April 12, 2022, PreQC No. IPCCO-22-13066 (PQ); Reviewed date: April 27, 2022, QC No. IPCCO-22-13066; Revised date: June 10, 2022, Manuscript No. IPCCO-22-13066 (R); Published date: June 20, 2022, DOI: 10.36648/2471-9803.8.9.084

Citation: Kizito O, Mary MR (2022) Factors Associated with Men’s Participation in Postpartum Family Planning: A Study of Kiswa Health Centre III, Kampala, Uganda. Crit Care Obst Gyne Vol:8 No:9

Abstract

Family Planning (FP) is an essential component of health care provided during the antenatal period, immediately after delivery and during the first year after childbirth. Evidence has it that short birth intervals of less than 15 months have been found to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes including induced abortions, miscarriages, preterm births, neonatal and child mortalities, still births and maternal depletion syndrome. Despite the evidence of close birth intervals being associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, many women are not using effective family planning methods. This is attributed to low men participation in postpartum family planning. In order to improve maternal health, strengthening male participation in family planning is an important public health initiative. This study aimed at assessing factors associated with men’s participation in postpartum family planning, taking a case of family planning services provision at Kiswa Health Center III, Nakawa division, Kampala district. This study aimed at assessing factors associated with participation of men in postpartum family at Kiswa Health center III, Kampala.

The study was a cross sectional study involving collection of quantitative data. Systematic random sampling was used to select study participants. Data was collected using semi structured questionnaires dveeloped from reviewed literature. The data entry and cleaning was performed using EpiData version 12. The data was analyzed using Stata version 14. Proportions, measures of central tendency (mean, median and mode) and measures of association (P values, Odds Ratios and confidence intervals) were used to describe the study subjects. Results were summarized into graphs, tables, pie charts. Study findings will be published in scientific journals and conferences.

The average age of study respondents was 39.8 years, about half 49.6% (55.5/371) with 2-4 children. About 51.7% (51.8/371) of the study respondents were married, 39.8% (148/371) Catholics and 43.4% (161/371) reached tertiary level of education. 80.0% (297/371) reported to participate in postpartum family planning. On multi-variate regression analysis of the factors associated with male involvement in family planning, approval of family planning use, knowledge on family planning and information source were found to be significantly associated with male involvement in family planning. Study respondents who approved family planning use at home were 15.5 times more likely to get involved in family planning services as compared to those who didn’t approve family planning at a 95% confidence interval. Those who knew about family planning were 3.65 times more likely to participate in family planning and those whose source of information was a television were 0.07 times less likely to get involved in family planning.

Conclusively, there was a generally high level of male involvement in postpartum family planning in comparison with the national levels. Approval of family planning at home increased the likelihood of men’s participation in family planning.

https://marmaris.tours

https://getmarmaristour.com

https://dailytourmarmaris.com

https://marmaristourguide.com

https://marmaris.live

https://marmaris.world

https://marmaris.yachts

Keywords

Postpartum family planning; Men’s participation; Kampala

Introduction

Family Planning (FP) is an essential component of health care provided during the antenatal period, immediately after delivery and during the first year after childbirth [1].The Family Planning 2020 (FP 2020) initiative is a global movement that supports this right and therefore the rights of women and girls to decide freely and for themselves whether, when, and how many children they want to have. Postpartum Family Planning (PPFP) is defined as the prevention of unintended pregnancy and closely spaced pregnancies through the first 12 months following childbirth. This also includes pregnancies that ended with abortion [2].

Evidence has it that short birth intervals of less than 15 months have been found to be associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes including induced abortions, miscarriages, preterm births, neonatal and child mortalities, still births and maternal depletion syndrome [3]. Postpartum contraceptive use is not only important to reduce unintended pregnancies and pregnancies that are too closely spaced, but it also improves the health of the woman, her child and family [4]. World Health Organization recommends adoption of postpartum contraceptives not only for reduction of unplanned pregnancies, but also to improve maternal and child well-being.

Despite the evidence of close birth intervals being associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes, many women are not using effective family planning methods. This is attributed to low men participation in postpartum family planning. Reproductive health issues are an inclusive concern for both men and women. In order to improve maternal health, strengthening male participation in family planning is an important public health initiative [5]. Research suggests that spousal communication and male involvement in decision making can positively influence family-planning use and continuation.

According to World Health Organization report 2017, themajor inhibitors of male involvement in postpartum family planning included negative perception and lack of spousal support among other things. This study aims at assessing factors associated with men’s participation in postpartum family planning, taking a case of family planning services provision at Kiswa Health Center III, Nakawa division, Kampala district.

Background of the study

In many contexts worldwide, men tend to be the decision makers within families and heavily influence decisions regarding contraception and STI prevention and family planning. Male involvement in family planning services is associated with maternal and child motility. Data from Kenya demographic and health survey of 2008-09 indicated that the adjusted odds ratio after controlling for other factors shows that women whose husbands attended family planning services were more likely to have skilled birth attendance than those whose husbands did not (AOR, 1.9; 95 percent CI, 1.09-3.32).

In order to improve maternal health, strengthening male participation in family planning is an important global public health initiative. The importance of involving men in reproductive, maternal and child health programs is increasingly recognized globally. Unfortunately, most of maternal and child health services around the globe do not actively engage expectant fathers and fathers of young children and few studies have been conducted on the challenges, benefits and opportunities for involving fathers. In a qualitative study of policy makers and practitioners carried out in the pacific reported that greater men’s involvement would result in a range of benefits for maternal and child health, primarily through greater access to services and interventions for women and children [6]. Perceived challenges to greater father involvement included sociocultural norms, difficulty engaging couples before first pregnancy, the physical layout of clinics, and health worker workloads and attitudes.

In Africa, many countries have made significant progress on improving reproductive, maternal, newborn and child health in the past ten years. However, there’s still a high burden of poor maternal, neonatal and child health. A community based crosssectional study carried out among 620 married men in Ethiopia revealed that 12.5% were directly involved in the use of family planning using a male contraceptive method, and about 60.0%of males were involved in family planning through spousal communication and approval. Being educated (AOR=1.64; 95% CI: (1.12-2.62)), having an educated partner (AOR=1.77; 95% CI: (1.17-2.94)), having a positive attitude towards family planning (AOR=2.27; 95% CI: (1.53-3.36)), discussing with wife (AOR=2.51; 95% CI: (1.69-3.72)) and having adequate knowledge about family planning [AOR=1.92; 95% CI: (1.28-2.87)) were positively associated with male involvement in family planning utilization whereas having more than three children (AOR=0.32; 95% CI: (0.15-0.70)) was negatively associated with male involvement in family planning utilization [7].

An integrative review of studies carried out in the continent on male involvement in family planning shows that religion, large family size, culture, fear of side effect, access and exposure to information, attitudes, norms and self-efficacy and interaction with a health care provider are determinants of male involvement in family planning use [8]. These findings reveal that interventional programs by health care providers and intensive education to men will positively increase prevalence of family planning use across the continent. It’s recommended to involve religious leaders in education as well.

Family planning programs have made vast progress in many regions of sub-Saharan Africa [9]. Nevertheless, there are numerous barriers hindering its smooth progress. A study exploring barriers to and facilitators of using family planning services among HIV positive men in Nyanza Province, Kenya reveals different barriers for male involvement in family planning services. These include; concerns about side effects of contraceptives, lack of knowledge about contraceptive methods, myths and misconceptions including fear of infertility, structural barriers such as staffing shortages at HIV clinics, and a lack of male focus in family planning methods and service delivery [10]. A cross sectional study conducted in Kenya demonstrated that 48% of the respondents were not involved at all in family planning and only 6% of men were using a family planning method. The age of respondents, educational level, number of children, and type of marriage, knowledge and ease of access to family planning services were all significantly associated with male involvement. Having no education made a man 89% less likely to be highly involved in family planning (OD 0.117; 95% CI: 0.03-0.454).

Unmet need for family planning exceeds 33% in Uganda. This figure can be decreased by promoting male involvement in family planning. Despite this, male involvement in family planning services is as well low in the country [11]. Male disapproval of use of family planning by their female partners and misconceptions about side effects are barriers to family planning in Uganda. In a study to assess the knowledge and use of family planning among men in rural Uganda indicates that relatively few men reported knowing about the most effective reversible contraceptive methods, intrauterine devices and implants (16%).

There is scanty literature regarding male involvement in family planning in Kampala [12]. However, available information reveals that the practice is generally low. To increase male involvement in family planning services in Kampala, a study by Gopal suggests that a 'bottom-up' approach to male involvement. The approach should emphasize solutions developed by or in tandem with community members, specifically, fathers and community leaders who are privy to the social norms, structures, and challenges of the community. This study intends to explore the factors associated with participation of men in postpartum family planning services in Kampala.

Research questions

• What is the proportion of men participating in postpartum family planning in Kiswa HCIII, Kampala district?

• What individual factors influence participation of men in postpartum family planning in Kiswa HCIII, Kampala district?

• What social cultural factors influence participation of men in postpartum family planning in Kiswa HCIII, Kampala district?

• What health system factors influence participation of men in postpartum family planning in Kiswa HCIII, Kampala district?

Literature Review

Introduction

Family planning issues are an inclusive concern for both men and women. In order to improve maternal health, strengthening male participation in family planning is an important public health initiative. Yet, men are still the main decision-makers in the family in Uganda, especially in the urban community. There is little concrete evidence of the extent of male participation in family planning and its associated factors in Uganda. This chapter reviews, compares, contrasts and attempts to explain differences in different study findings of other similar studies. It is sub-divided into introduction, male participation in family planning, individual factors influencing participation of men in family planning, socio-cultural factors and health system factors.

Male participation in family planning

Various studies have shown that family planning adoption is likely to be more effective for women when men are actively involved around the globe [13]. Application of trans-theoretical model to assess male involvement in family planning in Vietnam shows that 25.8% of men were in the pre-contemplation stage, 10.5% of men were in the contemplation/preparation stages and 63.7% of men were in the action/maintenance stages of behavior change. This implies that over 60% of study respondents participated in family planning. However, findings from this study are contrary to findings in a cross sectional study by Grimley, which shows that only 12.5% of the male were involved in family planning. Nevertheless, the former study only focused on only condom use as a family planning option, hence difference in study findings. Some studies like reveal 64.4% male involvement in family planning which is closer to findings of [13]. In this study, marital status, employment status and knowledge about family planning of respondents were positively associated with male involvement in family planning (p-value< 0.05). Health education and sensitization messages ought to be implemented in both studies to further increase male involvement in family planning.

A quantitative descriptive cross sectional study carried out in Nepal show that over half of the husbands (59.4%) were involved in giving advice, supporting to reduce the household work burden, and providing financial support for family planning. After adjustment for other covariates, economic autonomy was associated with lower likelihood of discussion with husband during pregnancy, while domestic decision-making autonomy was associated with both lower likelihood of discussion with husband during pregnancy and the husband's involvement in family planning [14]. This implies that interventions geared towards increasing male involvement in family planning services should target discussion of husband with wife more especially economically autonomous couples.

A cross sectional study carried out in India shows that only 10% subjects used condoms. More than half the subjects from middle socio-economic status used pills and only 25% from low Socio-economic status used them. Whereas a similar study carried out in Uttar Pradesh shows that only 3% of the couples used pills [15]. It is however important to note that the former study was carried out among both married and un married study respondents while the later was carried out among the married. Almost 70% of the subjects actively practiced other family planning methods in a descriptive cross sectional study carried out by Demissie. Contrary to this, 20% subjects in a study in Uttar Pradesh reported of practicing sterilization. 50% of middle Socio-economic status and 18% of high Socio-economic status people used Copper-T IUD. On the other hand, 1% of the subjects in Uttar Pradesh used IUD. Condoms and pills were most commonly used by most of the subjects as they were convenient (53%), affordable (48%) and readily available (47%) in a study by T. On the contrary, a study conducted in Pakistan showed that condom was the most known method of contraception (27.3%) followed by withdrawal, injection and pills.

Usage of family planning services in developing countries more especially in Africa has been found to avert unintended pregnancies, and drastically reduce maternal and child mortality. Men as the main decision-makers in most of African families have an important role to play towards acceptance of family planning methods; however, its usage still remains low [16]. A cross sectional study carried out in Ghana observed that majority of respondents in the studied area (83.26%) accept the act of male spouses accompanying their partners for family planning services. This finding, however, was contrary to the findings from a study in the Kassena-Nankana District in the Northern part of Ghana where women opting to practice family planning must do so at considerable risk of social ostracism or familial conflict and not even thinking of male partners accompanying them to family planning clinic. Difference in study findings could be attributed to the fact that the former study was carried out in Tema Metropolis which is an urban setting with high education level as compared to study participants in the later study. As a result of these perceptions, male involvement in family planning remains lower than wanted across the continent [17].

Knowledge level of the study participants on family planning in a descriptive cross sectional study carried out in Ghana revealed that more than half of the men had sufficient knowledge about family planning. Respondents who knew a lot and sufficiently were 9 times and 5 times more likely respectively to be involved in family planning (AOR=8.79, 95% CI: 0.81-95.89) (AOR=4.93, 95% CI: 0.51-47.25). In a qualitative cross sectional study assessing male participation in family planning in Mpigi district Uganda, men had limited knowledge about family planning, family planning services. However, this was attributed to the fact that family planning services did not adequately meet the needs of men and spousal communication about family planning issues was generally poor. Continuous discussion of family planning issues between couples increases male involvement in family planning. A study by Minority shows that about sixty percent (60.8%) of respondents had discussed family planning with wives or a partner which was similar to a study by Thapa. A study by Minority revealed that among those who had ever attended a family planning clinic, the majority (54.61%) had attended once, which has similar findings to that in communities in Afar, Ethiopia where husbands’ involvement in family planning was about 42.2% [18].

In Uganda, unmet need for family planning remains high at 33%. Knowledge levels of men regarding family planning seems high (98%) with the most common method being a condom (72%). Despite high knowledge the utilization of family planning methods remains low (40%) [19]. This is not surprising: while women commonly access healthcare facilities for antenatal care and childhood immunization visits, men are far less likely to have healthcare needs that bring them to hospitals and clinics where they might encounter accurate family planning information hence low utilization. There have been some efforts to use media (radio, television, print ads, etc.) to increase male participation in family planning decision-making and use that have had positive results including in Uganda. A more recent examination of programs in Nigeria, Kenya, and Senegal that included exposure to family planning messages via mass media, print media, interpersonal communication, and community events also found some evidence that exposure to radio advertisements/programs increased men’s reported use of modern contraception. Interestingly, results also suggested that men who attended community events (e.g., Community Theater) and heard religious leaders speak favorably about family planning were also more likely to report use of modern contraception, two additional approaches that may be effective in areas like Nakaseke.

In a study by Dougherty carried out in Uganda, regarding side effects of contraception, many men could name specific side effects, and the side effects noted were consistent with those reported by men in qualitative studies. Given that more than two thirds of the married women in Uganda report that contraceptive decision-making is either undertaken jointly or exclusively by male partners, education efforts should continue to build the foundation of accurate knowledge about contraceptive side effects among men while also looking for ways to promote greater understanding about the ramifications of such side effects.

Individual factors influencing participation of men

Globally, different individual factors including age, sex, knowledge regarding family planning, personal attitudes and beliefs, etc have been found to be associated with male involvement in family planning. A quantitative cross sectional study carried out from coastal southern India shows that study subjects who had high knowledge were more likely (P<0.0001) to have vasectomy as compared to their counterparts who were considered to have low knowledge. Furthermore, most of the subjects were of the opinion that frequent pregnancies lead to health problems. In the later study, 70% of the subjects stated that their most common source of information about contraception was from friends (72%) followed by radio and television (70%). Findings from this study are contrary to findings in Nigeria where majority (45.1%) had heard of contraception from friends/partner followed by 25.5% who had heard it from hospitals. In another study in West Bengal 53%, (India) gained the information through friends and 56% from health workers. This is in concordance to study findings by Theny, et al. and implies that health care providers and modern means of communication and media have established greater awareness in the public.

In a cross sectional study by Teney, et al. shows that most of the men (87.8%) were aware of male contraception in the market with those from the lower Socio-economic status (86.9%) having almost equal awareness as compared to upper Socio-economic status (92.3%). This could be due to active awareness programs held in the community and also information about contraceptives. Similarly 97.5% of the men in a study in Maharashtra were aware of male contraception; namely condoms. Regarding ideal spacing, study participants belonging to upper socio-economic status (92.3%) knew about ideal spacing and interestingly, even in the low Socio-economic status, 86.9% subjects knew about the same in a study by Teney, et al. These findings suggest a requirement of further awareness program across different Sscio-economic strata to ensure involvement of men in family planning.

Educational status of male partner was found to be one factor for men´s involvement in family planning across the African continent. In a cross sectional study carried out in Malawi shows that those respondents who were unable to read and write AOR (95%CI)=8.55 (2.118, 34.531) and those in secondary education level AOR (95%CI)=2.39 (1.084, 5.260) were 8.6 and 2.3 times more likely to be involved in family planning service respectively as compared to those in higher education level. This result is consistent with the study done in Eastern Tigray, Ethiopia, in Kenya and Turkey. This is because individual concern could not be affected by education; moreover, this could be the low economic status and motivation of the individuals.

Source of information is also one significant factor for male involvement in family planning. In a study by Demissie, et al. radio as a source of information AOR (95%CI)=1.88 (1.016, 3.485) was 1.8 times more likely affected men to be involved in family planning than those did not have information on the radio. This result is consistent with the study done in Malegedo Town, Oromia, Ethiopia. Men´s approval for family planning is also strongly associated with men´s involvement in family planning. In a study by Demissie, et al. Those men who approved family planning for their partner in the later study AOR (95%CI)=0.07 (0.036, 0.134) were by 93% less likely to involve in family planning than those who did not approve family planning. This result is inconsistent with the study conducted in Bench Maji Zone, Ethiopia and Debre Markos, Ethiopia. This may be due to the accessibility of information and shared responsibility; that only female partners were taking responsibility for family planning.

Previous utilization of family planning is another key factor influencing male involvement. In a study carried out by Demissie, et al. indicates that female partners who used FP method previously AOR (95%CI)=3.20 (1.752, 5.834) were 3.3 times more likely to be involved in family planning than those did not use FP methods previously. This may be the experience sharing for male partners and shared responsibility. Because family planning could be affected by many factors such as gender, biological factors, socio cultural aspects of both the community and the partner, policy of the country, decision making of the partners and communication, the study could point out the possible barriers and solutions to have consent on family planning or a partner by involving male partners.

Side effects are potential physiological reactions to hormonal contraceptives and are not exactly borne of the social context like the other barriers like low knowledge, they have a particular significance in this socio-cultural context, and it is worth exploring how they nuance the other barriers. Side effects were reported to be a significant motivational barrier for the uptake and continuation of contraceptives in each focus group in married men in Uganda. Side effects, misconceptions, and stigma have a compounding effect on each other; in essence, side effects validate stigma and fuel misconceptions. Side effects such as prolonged bleeding, intrusive procedures, pain, and amenorrhea are inconvenient to the clients, and significantly diminish the perceived value clients place on family planning, especially when side effects legitimize social stigmas and disinformation circulates the community. Men’s attitude towards family planning as well influences their involvement. In a qualitative cross sectional study carried out among men in Uganda indicates that men believed issues related to pregnancy and childbirth were the domain of women. Involvement tended to be confined (to remove) strictly to traditional gender roles, with men's main responsibility being provision of funds. The women, on the other hand, were interested in receiving more support from their husband through planning, attendance to antenatal care and physical presence in the vicinity of where the birth was taking place [20].

Socio-cultural factors in luencing participation of men in family planning

Various socio-cultural factors like cultural misconceptions, religion, spousal communication, etc. In a descriptive cross sectional study to assess perceptions of family planning and reasons for low acceptance of No Scalpel Vasectomy (NSV) among married males of urban slums of Lucknow city, India indicates that majority (89.2%) of respondents had stated sociocultural barrier as one of the major cause for low acceptance of no scalpel vasectomy. Among these barriers majority 35.9% of the respondents stated that NSV leads to decrease in physical strength, followed by 35.0% respondents having personal beliefs that NSV is not needed because of the availability of other family planning methods. About 11.1% of the respondents also stated that NSV leads to decrease in physical strength. 6.4% of the respondents had also stated that prohibition in religion was also one of the factors associated with low acceptance of NSV. 5.5% of the respondents also stated that NSV is least popular and there is lack of publicity and awareness. There were few (1.2%) respondents who also believed that NSV affects the male sexual function. Similar findings were observed in a study done by Shafi and Mohan, et al. which showed that 22.0% of the participants believed on 'personal beliefs' of the individual as an important factor for low utilization of NSV. Similarly, in a study done in Uttar Pradesh by 'State Innovation in Family Planning Services Project Agency' (SIFPSA, 2014), showed that 6% of the respondents had stated prohibition in religion as one of the barrier for not accepting No Scalpel Vasectomy. About 14% also believed that NSV leads to decrease in physical strength and causes weakness.

In Africa, different studies show that the desire to have another child, lack of awareness, religious prohibition and fear of side effects, men’s attitudes towards FP use and others are among the socio-cultural factors for low involvement of males in FP services. In a cross sectional study carried out to in Northwestern Ethiopia indicates that men who had negative opinion about condom use with the believe that it reduces sexual potency were 2.13 times less likely to be involved in the use of FP services than those with positive opinion (AOR=2.13, 95% CI: 1.28-3.53, p-value=0.003). These findings are in line with studies by.

A study done in Tanzania indicated that men were feared that women would be unfaithful if allowed to use contraception. Furthermore, they believed that condoms were useful for the prevention of HIV/AIDS with prostitutes and did not associate use with FP.

The number of children is another factor that determines male involvement in family planning. A study by Wondim, et al. indicated that families who had more children enhanced male involvement.

Another key barrier to the men’s involvement in family planning is women’s perceptions of husbands’ opposition. Thus, a discussion between couples is fundamental for reproductive health and family planning use. It increases up taking and continuation of contraceptive use. A study by Wondim, et al. showed that discussion between couples about family planning increases the probability of male involvement in family planning. Open discussion promotes the chance of joint decisions on family size which then enhances male involvement. But in this study, only 46% of men discussed with their partner about family planning.

A study carried out by Wondim, et al. Showed that more than half of men had a negative attitude towards family planning and surprisingly nearly one-fourth of men agreed that males should not share the family planning method. This might contribute to the low contraceptive prevalence rate in the rural community of Ethiopia. A significant number of men in Africa seemed resistant to accept the use of FP for financial and religious reasons.

Health system factors in luence participation of men in family planning services

Various factors like accessibility of health facility, affordability of the services and availability health workers among others are the health system factors influencing participation of men in family planning services. A qualitative cross sectional study carried out among HIV Positive men in Nyanza province, Kenya shows that shortage of staff to provide the services was one of the key barriers. In the former study one study subject in the focus group discussion said that when there are stock outs of commodities, his wife world go to the pharmacy to buy the medication and have someone administer the injection which demotivated him from being involved in family planning services. Another man reported that condoms are sometimes out of stock at the health facility, and he must buy them. This demotivates men from being involved in family planning services.

Gender of health care provider is as well a factor influencing male involvement in family planning. A study by Sharma, et al. indicates that male were not involved in family planning services because services were being offered by male health workers. This implies that to improve the number of men who engage in family planning services, it is vital to recruit males as family planning providers and offering more family planning counseling for couples.

In a cross sectional study carried out in Ethiopia, of the total respondents, 352 (71.3%) of them discussed contraceptive methods with health care providers, and 269 (54.5%) visited healthcare facilities with their spouses within the last 12 months before this study because the facility was within 30 meters from their homes. About 45% never visited the health facility because it was over 30 meters from their homes. Bringing family planning services closer to the people may increase male involvement. An interventional study carried out by Chekole, et al. shows that when FP services were brought closer to the people through outreaches, male involvement increased from 32.9% to 79.4%. This implies that making family planning services more accessible increases on male involvement in the services.

Materials and Methods

Study design

This was an analytical cross sectional study. It involved collecting quantitative data using pre-tested semi structured questionnaires.

Study area

The study will be conducted at Kiswa Health Center III. Kiswa Health Center III is opposite Bugolobi shell, Kataza Cl and is located in Kampala District, Central Region and Uganda. Kiswa Health Center III has a length of 0.11 kilometers.

Kiswa is purposively selected because of its long-time work in offering sexual and reproductive health services, including family planning. Kiswa HC III is known to the researcher for having service data for Post-partum family planning utilization.

It’s also selected for convenience of finding men who are visiting the facility with their spouses for Post-partum family planning services.

Study population

The study population included men (15-50) yearsat Kiswa Health center III particularly those who have had or have partners with children.

Study unit

The study unit were men (15-50) years at Kiswa Health center III particularly those who have had or have partners with children.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria: Any man (15-50) years at Kiswa Health center III who has had or had a partner (s) with children was included in the study.

Exclusion criteria: Any man (15–50) years at Kiswa Health center III with a partner but has never had a child was excluded from the study.

Sample size determination

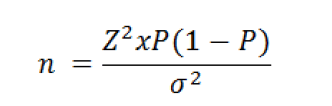

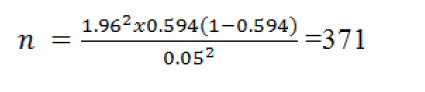

The sample size formula for Kish Leslie (1964) was used as expressed below,

Sample size,

Where Z is the standard normal deviate of 1.96 (95% confidence interval)

P=Number of women whose partners are involved in family planning services (59.4%).

D=level of precision (+/- 5%)

N=371 study respondents

Sampling technique and procedure

Systematic simple random sampling was used to select the study participants. This technique was easier to implement in the field given it being facility based. On average, thirty patients visited the facility to seek family planning services. To get the sampling interval the principal investigator divided 371 study respondents by 30, giving about 12. This implied that the principal investigator selected study respondents at an interval of twelve (every twelveth patient visiting the facility voluntarily participated in the study). Every first patient to participate in the study in each day was randomly selected by listing down all possible positions on pieces of paper and randomly selected. The selected number was the first person to participate in the study. The study took 30 days.

Variables

Dependent variable: Male participation in family planning services.

Independent variables: Socio-demographic factors these included respondents’ age, sex, occupation, economic status, type of dwelling, level of education. Individual factors these included age of respondents, level of education, knowledge regarding family planning, number of children, past experience, marital status, men’s attitude, occupation and monthly income. Socio-cultural factors these included cultural misconceptions, religion, spousal communication, peer influence and group membership. Health system factors these included accessibility to family planning services, affordability of the services, availability and acceptability of family planning services by study respondents.

Data collection tools and methods

A pre-tested semi structured questionnaire was used, employing quantitative methods of data collection. The questionnaire was developed from literature reviewed [19]. The questionnaire consisted of five sections. Section A composed of questions on socio-demographic characteristics of study respondents, section B consisted of questions regarding male participation in family planning, section C composed of individual factors, section D on socio-cultural factors and section E on health system factors. The tool was translated to Luganda since it is the pre-dominant language in the study area.

Data entry, analysis and presentation

Data was entered in Epi Data version 3.1; then it was transferred to Stata version 14 for analysis. Data was then cleaned in Stata, before analysis. Analysis was carried out at univariate, bivariate and multivariate levels. At univariate level, analysis was run for all the variables, and frequencies and percentages are presented using tables, pie charts and graphs. At bivariate level, the outcome variable was male participation in family planning. Logistic regressions were used to identify the significant associations between the outcome variable and the predictor variables using crude odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals as the measure of association. At multivariate level, variables that showed significant associations at bivariate analysis were included into the multivariate model. Results are presented in tables using adjusted odds ratios and their 95% confidence intervals to show significant associations between male participation inf amily planning services and various factors.

Quality controls

Selection and training of research assistants: The researcher selected competent research assistants and trained them on questionnaire administration and data collection. Meetings with the research assistants were held before, during and after data collection.

Pretesting of data collection tools: The questionnaires were pre-tested at Kiswa health center III. The pretested tools were updated to remove any inconsistencies. The questionnaires were translated to Luganda, the most pre dominant language adopted and spoken in Kataza zone.

Field supervision: Supervision of research assistants at all times was done by the researcher to ensure all the required data is collected from all the respondents.

Field editing of data collected: Editing of data collection tools were appropriate to ensure all relevant information with regards to the objectives of the study was collected.

Ethical considerations

Permission was sought from Uganda Martyrs’ University, Institutional review board. Permission was also sought from administration of Kiswa Health center III and Kampala Capital City Authority. Individual study respondents were also approached to obtain their consent to carry out the study. All information provided by the respondents is confidential.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of tudsy respondents

The average age of study respondents was 39.8 years and 32.2 years for spouses, about half 49.6% (55.5/371) with 2-4 children. About 51.7% (51.8/371) of the study respondents were married, 39.8% (148/371) Catholics and 43.4% (161/371) reached tertiary level of education (Table 1).

| variable | Frequencies (N=371) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age of study respondent (years) | ||

| 20-29 | 89 | 24 |

| 30-39 | 121 | 32.6 |

| 40-49 | 70 | 18.9 |

| 50+ | 91 | 24.5 |

| Age of spouse (years) | ||

| 18-29 | 184 | 49.6 |

| 30-39 | 113 | 30.5 |

| 40+ | 74 | 19.9 |

| Number of children | ||

| 0-1 | 94 | 25.3 |

| 2-4 | 206 | 55.5 |

| 5+ | 71 | 19.2 |

| Number of children expected | ||

| 2-4 | 203 | 54.7 |

| 5+ | 168 | 45.3 |

| Spouse’ educational level | ||

| Primary | 125 | 33.7 |

| Secondary | 172 | 46.4 |

| Tertiary | 74 | 19.9 |

| Spouse’ occupation | ||

| Business | 190 | 51.2 |

| Civil servant | 53 | 14.3 |

| Peasant | 128 | 34.5 |

| Marital status | ||

| Co-habiting | 167 | 45 |

| Divorced | 12 | 3.2 |

| Married | 192 | 51.8 |

| Respondent’s religion | ||

| Anglican | 101 | 27.2 |

| Born again | 71 | 19.1 |

| Catholic | 148 | 39.9 |

| Muslim | 51 | 13.8 |

| Tribe of respondent | ||

| Luo | 35 | 9.4 |

| Muganda | 81 | 21.8 |

| Munyankole | 57 | 15.4 |

| Musoga | 54 | 14.6 |

| **Others | 144 | 38.8 |

| Respondent’s education level | ||

| Primary | 67 | 18.1 |

| Secondary | 143 | 38.5 |

| Tertiary | 161 | 43.4 |

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of study respondents.

Proportion of men participating in postpartum family planning

Majority of the study respondents 80.0% (297/371) reported to participate in postpartum family planning (Table 2).

| Variable | Frequencies (N=371) | Percentages (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Do you participate in FP? | ||

| No | 74 | 20 |

| Yes | 297 | 80 |

Table 2: The reported to participate in postpartum family planning (FP).

Individual factors associated with male participation in postpartum family planning

On bi-variate analysis of the factors associated with postpartum family planning, respondents’ age, spouses’ age, under of children by the respondent, number of children expected by the family, spouse’ education level, spouse’s occupation, respondents’ education level, knowledge on family planning and source of information were found to be significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study respondents who were aged 50 years and above (COR=0.37, CI=0.18-0.76, P-value=0.007) were 0.37 less likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Respondents’ spouses aged 40 years and above (COR=0.30, CI=0.15-0.57, P-value=0.00) were 60% less likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Those who had 5 children and above (COR=0.27, CI=0.13-057, P-value=0.001) were 0.27 less likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Study participants whose spouses reached atleast secondary level of education (COR=2.52, CI=1.40-4.53, P-value=0.002) were 2.52 more likely to participate in postpartum family planning (Table 3).

| Variable | Male involvement in FP | COR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No 74 (20.0) | Yes 297 (80.0) | |||

| Age of study respondent (years) | ||||

| 20-29 | 13 (14.6) | 76 (85.4) | ||

| 30-30 | 19 (15.7) | 102 (84.3) | 0.92 (0.43-1.97) | 0.83 |

| 40-49 | 13 (18.6) | 57 (81.4) | 0.75 (0.32-1.74) | 0.5 |

| 50+ | 29 (31.9) | 62 (68.1) | 0.37 (0.18-0.76) | 0.007* |

| Age of spouse (years) | ||||

| 18-29 | 23 (12.5) | 161 (87.5) | ||

| 30-39 | 27 (23.9) | 86 (76.1) | 0.46 (0.25-0.84) | 0.01* |

| 40+ | 24 (32.4) | 50 (67.6) | 0.30 (0.15-0.57) | 0.00* |

| Number of children | ||||

| 0-1 | 15 (16.0) | 79 (84.0) | ||

| 4-Feb | 30 (14.6) | 176 (85.4) | 1.11 (0.57-2.19) | 0.75 |

| 5+ | 29 (40.9) | 42 (59.1) | 0.27 (0.13-0.57) | 0.001* |

| Number of children expected | ||||

| 4-Feb | 29 (14.3) | 174 (85.7) | ||

| 5+ | 45 (26.8) | 123 (73.2) | 0.46 (0.27-0.77) | 0.003* |

| Spouse’s education level | ||||

| Primary | 35 (28.0) | 90 (72.0) | ||

| Secondary | 23 (13.4) | 149 (86.6) | 2.52 (1.40-4.53) | 0.002* |

| Tertiary | 16 (21.6) | 58 (78.4) | 1.41 (0.72-2.78) | 0.32 |

| Spouse’ occupation | ||||

| Business | 30 (15.8) | 160 (84.2) | ||

| Civil servant | 12 (22.6) | 41 (77.4) | 0.64 (0.30-1.36) | 0.25 |

| Peasant | 32 (25.0) | 96 (75.0) | 0.56 (0.32-0.98) | 0.04* |

| Marital status | ||||

| Co-habiting | 26 (15.6) | 141 (84.4) | ||

| Divorced | 3 (25.0) | 9 (75.0) | 0.55 (0.14-2.18) | 0.4 |

| Married | 45 (23.4) | 147 (76.6) | 0.60 (0.35-1.03) | 0.06 |

| Respondent’s religion | ||||

| Anglican | 18 (17.8) | 83 (82.2) | ||

| Born again | 17 (23.9) | 54 (76.1) | 0.69 (0.33-1.45) | 0.33 |

| Catholic | 31 (21.0) | 117 (79.0) | 0.82 (0.43-1.56) | 0.54 |

| Muslim | 8 (15.7) | 43 (84.3) | 1.17 (0.47-2.90) | 0.74 |

| Respondent’s tribe | ||||

| Luo | 4 (11.4) | 31 (88.6) | ||

| Muganda | 15 (18.5) | 66 (81.5) | 0.57 (0.17-1.85) | 0.35 |

| Munyankole | 11 (19.3) | 46 (80.7) | 0.54 (0.16-1.85) | 0.33 |

| Musoga | 8 (14.8) | 46 (85.2) | 0.74 (0.21-2.68) | 0.65 |

| *Other | 36 (25.0) | 108 (75.0) | 0.39 (0.13-1.17) | 0.09 |

| Respondent’s educ level | ||||

| Primary | 24 (35.8) | 43 (64.2) | ||

| Secondary | 30 (21.0) | 113 (79.0) | 2.10 (1.11-4.00) | 0.02* |

| Tertiary | 20 (12.4) | 141 (87.6) | 3.93 (1.98-7.80) | 0.000* |

| Knows FP | ||||

| No | 40 (87.0) | 6 (13.0) | ||

| Yes | 34 (10.5) | 291 (89.5) | 57.1 (22.5-144.4) | 0.00* |

| Source of information | ||||

| Health worker | 4 (3.2) | 122 (96.8) | ||

| Newspaper/parent/radio | 5 (5.9) | 80 (94.1) | 0.52 (0.14-2.01) | 0.35 |

| television | 25 (21.9) | 89 (78.1) | 0.12 (0.04-0.35) | 0.000* |

| Too many children strain family | ||||

| Agree | 54 (17.2) | 260 (82.8) | ||

| Disagree | 20 (35.1) | 37 (64.9) | 0.38 (0.21-0.71) | 0.002* |

| Condom use doesn’t decreases sexual pleasure | ||||

| Agree | 36 (11.5) | 276 (88.5) | ||

| disagree | 38 (64.4) | 21 (35.6) | 0.07 (0.38-1.14) | 0.08 |

*Statistically significant P-value<0.05

Table 3: Individual factors associated with family planning.

Socio-cultural factors associated with male participation in postpartum family planning

Upon bi-variate analysis of the socio-cultural factors associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning, discussion with spouse, encouraging spouse to utilize family planning, approval of family planning use in family, were found to be significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study participants who discussed about family planning with their spouses (COR=58.5, CI=27.7-123.7, P-value=0.00) were 58.5 times more likely to get involved in family planning than those who didn’t discuss. Those who encouraged spouses to use family planning (COR=79.6, CI=32.3, P-value=0.00) were 79.6 more likely to get involved in family planning. Participants who approved family planning (COR=164.4, CI=60.32-448.0, P-value=0.00) were 164.4 more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning (Table 4).

| Variable | Male involvement in FP | COR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No 74 (20.0) | Yes 297 (80.0) | |||

| Discuss about FP with spouse | ||||

| No | 55 (79.7) | 14 (20.3) | ||

| Yes | 19 (6.3) | 283 (93.7) | 58.5 (27.7-123.7) | 0.00* |

| Decision maker | ||||

| Both | 53 (20.0) | 212 (80.0) | ||

| Wife | 6 (15.0) | 34 (85.0) | 1.42 (0.57-3.55) | 0.46 |

| Myself | 15 (22.7) | 51 (77.3) | 0.85 (0.44-1.63) | 0.62 |

| Encouraged spouse to use FP | ||||

| No | 68 (64.8) | 37 (35.2) | ||

| Yes | 6 (2.3) | 260 (97.7) | 79.6 (32.3-196.5) | 0.00* |

| Approved FP use in family | ||||

| No | 69 (75.0) | 23 (25.0) | ||

| Yes | 5 (1.8) | 274 (98.2) | 164.4 (60.32-448.0) | 0.00* |

| Religion determines FP | ||||

| No | 50 (19.1) | 212 (80.9) | ||

| Yes | 24 (22.0) | 85 (78.0) | 0.84 (0.48-1.44) | 0.52 |

| Culture determines FP | ||||

| No | 60 (20.4) | 234 (79.6) | ||

| Yes | 14 (18.2) | 63 (81.8) | 1.15 (0.61-2.20) | 0.66 |

*Statistically significant P-value<0.05

Table 4: Socio-cultural factors associated with male involvement in family planning.

Health systems factors associated with men’ participation in family planning

On bi-variate analysis of the health system factors associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning, cost of FP services at health facilities, affordability of the family planning services at health facilities, availability and service provider were found to be significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study participants who reported that family planning services at the facility were free (COR=3.60, CI=1.86-6.96, P-value=0.00), were 3.6 more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Those who reported that services were affordable (COR=4.28, CI=1.34-13.68, P-value=0.01) were 4.28 more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Study participants who reported that services were always available (COR=8.41, COR=4.33-16.32, P-value=0.00) were 8.41 more likely to participate in family planning. Study participants who reported a VHT as a family planning provider (COR=0.08, CI=0.02-0.33, P-value=0.00) were 92% less likely to participate in family planning at 95% confidence interval (Table 5).

| Variable | Male involvement in FP | COR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No 74 (20.0) | Yes 297 (80.0) | |||

| Health system factors | ||||

| Distance from home to facility | ||||

| <500 meters | 51 (22.9) | 172 (77.1) | ||

| >500 meters | 23 (15.5) | 125 (84.5) | 1.61 (0.94-2.78) | 0.09 |

| FP services at facility are free | ||||

| No | 19 (42.2) | 26 (57.8) | ||

| Yes | 55 (16.9) | 271 (83.1) | 3.60 (1.86-6.96) | 0.00* |

| FP services are affordable | ||||

| No | 6 (50.0) | 6(50.0) | ||

| Yes | 68 (18.9) | 291 (81.1) | 4.28 (1.34-13.68) | 0.01* |

| FP services are always available | ||||

| No | 27 (58.7) | 19 (41.3) | ||

| Yes | 47 (14.5) | 278 (85.5) | 8.41 (4.33-16.32) | 0.00* |

| FP service provider at the facility | ||||

| HW | 66 (18.3) | 294 (81.7) | ||

| VHT | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 0.08 (0.02-0.33) | 0.00* |

| FP service provider gender | ||||

| Female | 67 (21.3) | 248 (78.7) | ||

| Male | 7 (12.5) | 49 (87.5) | 1.89 (0.82-4.37) | 0.14 |

| Gender comfortable with | ||||

| Female | 56 (20.4) | 218 (79.6) | ||

| Male | 18 (18.6) | 79 (81.4) | 1.13 (0.62-2.03) | 0.69 |

| FP provider is ever rude | ||||

| No | 50 (17.8) | 231 (82.2) | ||

| Yes | 24 (26.7) | 66 (73.3) | 0.60 (0.34-1.04) | 0.07 |

Table 5: Health systems factors associated with male involvement in family planning.

Multivariable regression analysis of the factors associated with male involvement in family planning

On multi-variate regression analysis of the factors associated with male involvement in family planning, approval of family planning use, knowledge on family planning and information source were found to be significantly associated with male involvement in family planning. Study respondents who approved family planning use at home (Adj OR=16.5, CI=10.65-25.6, Adj P-value=0.00) were 15.5 times more likely to get involved in family planning services as compared to those who didn’t approve family planning at a 95% confidence interval. Respondents who knew about family planning (Adj OR=3.65, CI=1.76-8.54, Adj P-value=0.04) were 3.65 times more likely to participate in family planning at a 95% confidence interval. Those whose source of information was a television (Adj OR=0.07, CI=0.01-0.66, Adj P-value=0.02) were 0.07 times less likely to get involved in family planning (Table 6).

| Variable | Male involvement in FP | Adj OR (95% CI) | Adj P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No 74 (20.0) | Yes 297 (80.0) | |||

| Individual factors | ||||

| Age of study respondent (years) | ||||

| 20-29 | 13 (14.6) | 76 (85.4) | ||

| 30-30 | 19 (15.7) | 102 (84.3) | 0.49 (0.03-7.49) | 0.61 |

| 40-49 | 13 (18.6) | 57 (81.4) | 0.09 (0.00-4.32) | 0.23 |

| 50+ | 29 (31.9) | 62 (68.1) | 0.07 (0.00-3.89) | 0.2 |

| Age of spouse (years) | ||||

| 18-29 | 23 (12.5) | 161 (87.5) | ||

| 30-39 | 27 (23.9) | 86 (76.1) | 0.92 (0.12-6.99) | 0.94 |

| 40+ | 24 (32.4) | 50 (67.6) | 8.41 (0.41-171.9) | 0.17 |

| Number of children | ||||

| 0-1 | 15 (16.0) | 79 (84.0) | ||

| 4-Feb | 30 (14.6) | 176 (85.4) | 0.81 (0.06-10.28) | 0.87 |

| 5+ | 29 (40.9) | 42 (59.1) | 4.59 (0.10-20.5) | 0.43 |

| Number of children expected | ||||

| 4-Feb | 29 (14.3) | 174 (85.7) | ||

| 5+ | 45 (26.8) | 123 (73.2) | 0.67(0.10-4.54) | 0.67 |

| Spouse’s educ level | ||||

| Primary | 35 (28.0) | 90 (72.0) | ||

| Secondary | 23 (13.4) | 149 (86.6) | 2.46(0.27-22.6) | 0.43 |

| Tertiary | 16(21.6) | 58 (78.4) | 0.44(0.04-5.54) | 0.53 |

| Spouse’ occupation | ||||

| Business | 30 (15.8) | 160 (84.2) | ||

| Civil servant | 12 (22.6) | 41 (77.4) | 0.23 (0.02-2.60) | 0.24 |

| Peasant | 32 (25.0) | 96 (75.0) | 1.87 (0.25-14.03) | 0.54 |

| Respondent’s educ level | ||||

| Primary | 24 (35.8) | 43 (64.2) | ||

| Secondary | 30 (21.0) | 113 (79.0) | 2.89 (0.38-22.3) | 0.31 |

| Tertiary | 20 (12.4) | 141 (87.6) | 2.08 (0.22-19.74) | 0.52 |

| Socio-Cultural Factors | ||||

| Discuss about FP with spouse | ||||

| No | 55 (79.7) | 14 (20.3) | ||

| Yes | 19 (6.3) | 283 (93.7) | 2.08 (0.24-18.0) | 0.51 |

| Encouraged spouse to use FP | ||||

| No | 68 (64.8) | 37 (35.2) | ||

| Yes | 6 (2.3) | 260 (97.7) | 1.70 (0.12-24.66) | 0.7 |

| Approved FP use in family | ||||

| No | 69 (75.0) | 23 (25.0) | ||

| Yes | 5 (1.8) | 274 (98.2) | 16.5(10.65-25.6) | 0.00* |

| Know FP | ||||

| No | 40 (87.0) | 6 (13.0) | ||

| Yes | 34 (10.5) | 291 (89.5) | 3.65 (1.76-8.54) | 0.04* |

| Source of info | ||||

| Health worker | 4 (3.2) | 122 (96.8) | ||

| Newspaper/parent/radio | 5 (5.9) | 80 (94.1) | 0.42 (0.04-4.14) | 0.46 |

| Television | 25 (21.9) | 89 (78.1) | 0.07 (0.01-0.66) | 0.02* |

| Too many children strain family | ||||

| Agree | 54(17.2) | 260 (82.8) | ||

| Disagree | 20(35.1) | 37 (64.9) | 1.27 (0.11-14.6) | 0.85 |

| Health System Factors | ||||

| FP services at facility are free | ||||

| No | 19 (42.2) | 26 (57.8) | ||

| Yes | 55 (16.9) | 271 (83.1) | 1.02 (0.14-7.56) | 0.99 |

| FP services are affordable | ||||

| No | 6 (50.0) | 6 (50.0) | ||

| Yes | 68 (18.9) | 291 (81.1) | 4.37 (0.16-11.88) | 0.38 |

| FP services are always available | ||||

| No | 27 (58.7) | 19 (41.3) | ||

| Yes | 47 (14.5) | 278 (85.5) | 3.39 (0.48-23.95) | 0.22 |

| FP service provider at the facility | ||||

| HW | 66 (18.3) | 294 (81.7) | ||

| VHT | 8 (72.7) | 3 (27.3) | 0.09 (0.00-6.510) | 0.27 |

*Statistically significant Adj P-value<0.05

Table 6: Multivariable regression analysis of the factors associated with male involvement in family planning.

Discussion

Proportion of men participating in postpartum family planning

Majority of the study respondents (80.0%) reported to participate in postpartum family planning. This is slightly higher than the national level of male involvement in postpartum family planning which currently stands at 73%. This could be because it was carried out in an urban setting where people have higher knowledge on postpartum family planning hence involvement. It should however be noted that the findings are lower than findings by Bodin, et al. where participation levels were 94%. The latter study was however carried out in Sweden, a high income country. Ministry of health and its partners should design sensitization programs geared towards increasing male involvement in family planning in the study area.

Individual factors associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning

Spouse’s education level was significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study respondents whose spouses had reached at least secondary level were more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Upon adjustment for co-founders however, the associated became not statistically significant. This could be because spouses with higher education levels had high knowledge on family planning hence influencing male involvement. Findings from this study are in agreement with findings in a study by Nzokirisha, et al. which also revealed a positive significant association between spouse’s education level and male involvement in postpartum family planning at bivariate level of analysis.

The study further revealed that study respondents who were 50 years and above were less likely to participate in postpartum family planning. This could be because such people have old spouses who may not be in the reproductive age. The findings are in agreement with findings by Silverman, et al. where older study participants were less likely to get involved in postpartum family planning as well.

Half of the study respondents reported to be married. This may imply regular contact with their spouses hence influencing them to participate in family planning. Unlike this study, a cross sectional study by Dral, et al. indicates a significant positive association between being married and involvement in postpartum family planning. More than quarter (43.4%) of the study respondents reached tertiary level of education. High education levels may signify high knowledge about family planning hence male involvement. Findings from this study indicate that study participants who had attained secondary level of education were more likely to be involved in postpartum family planning. This could be attributed to increased knowledge levels about importance of family planning. The findings are in line with findings by Nzokirisha, et al. where there were also significant positive associations between education level and male involvement in postpartum family planning.

Knowledge about postpartum family planning was strongly associated with male involvement. Study respondents who had knowledge about postpartum family planning were more likely to get involved in family planning. This could be attributed to the fact more knowledge regarding family planning implies that the study respondents know the benefits of getting involved in family planning. Findings from this study are in agreement with findings in a study by August, et al. which also revealed a similar association. Public health programs should therefore leverage on increasing the knowledge of men about postpartum family planning which will eventually lead to their involvement in family planning. Information source about family planning was also significantly associated with male involvement in family planning. Study respondents who received information about family planning from a television screen were 88% less likely to participate in postpartum family planning. Similar associations have been observed in different studies, with no clear explanation as to why. The associations however became not statistically significant after multi-variable logistic regression analysis.

Study respondents who disagreed to the statement that too many children strain family were less likely to participate in postpartum family planning. This could be attributed to the fact that they are biased about the whole issue of family planning hence negative attitude. The association remained statistically significant even after multivariable regression analysis. Findings from this study are in agreement with findings in a study by Butoo and Mburu, et al. which reveals that respondents’ attitude was significantly associated with male’s involvement in postpartum family planning.

Socio-cultural factors associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning

Discussion with spouse about family planning was significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study respondents who discussed about family planning were more likely to get involved in it. This is can because the information they obtain from their spouses about family planning drives them to participate in it. Findings from this study are in line with findings in a study by. It is very vital to always discuss reproductive health issues as a family such that healthy decisions are taken up as a family and not as an individual.

Respondent’s approval of family planning at family level was also significantly associated with male’s involvement. Participants who approved family planning at family level were 164.4 more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. These study findings are in agreement in findings by Chekole, et al. where male’s approval was also significantly associated with male involvement. This could be because approval comes with satisfaction about the issue which in turn drives to actual participation.

Health systems factors associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning

Cost of family planning services at health facilities was significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study respondents who reported that family planning services at the health facility were free were more likely to get involved in family planning. Conventionally, people will also opt for cheapest services available. Therefore, free family planning services drive men to participate. Interventions should therefore be geared towards ensuring that family planning services in all health facilities are either free or as cheap as possible in order to drive men to participate. Findings from this study are in line with findings in a study by Shattuk, et al. where there was a statistically significant association between male involvement in family planning and cost of the service.

Availability of family planning services was also significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study respondents who reported that the services were always available every time they visited were more likely to participate in family planning. Sometimes men get demoralized when they go to receive family planning services at a health center and only to find that they aren’t offered. This implies that strategies have to be designed to ensure that health facilities provide family planning services 24 hours. Findings from this study are in agreement with findings in a study by Santero, et al. where there was a significant association between male involvement in postpartum family planning and availability of family planning services at the health facilities.

The study further revealed that the family planning service provider was key in ensuring male involvement in postpartum family planning. Study respondents who reported a Village Health Team (VHT) as a service provider were 92% less likely to participate in family planning. This could be because they passive VHTs as less skilled, less knowledgeable about the subject matter. It is as well advisable to always seek services from a skilled service provider regarding family planning.

Conclusion

There were generally high levels of male involvement in postpartum family planning in comparison with the national levels.

Individual factors that were significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning included respondent’s age, spouse’s age, number of children and education level. Study respondents who were aged 50 years and above were less likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Respondents’ spouses aged 40 years and above were 60% less likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Those who had 5 children and more were 0.27 less likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Study participants whose spouses reached atleast secondary level of education were 2.52 more likely to participate in postpartum family planning.

Socio-cultural factors significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning include, discussion with spouse, encouraging spouse to utilize family planning and approval of family planning use in family. Study participants who discussed about family planning with their spouses were 58.5 times more likely to get involved in family planning than those who didn’t discuss. Those who encouraged spouses to use family planning were 79.6 more likely to get involved in family planning. Participants who approved family were 164.4 more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning.

Health system factors significantly associated with male involvement in postpartum family planning included, cost of FP services at health facilities, affordability of the family planning services at health facilities, availability and service provider. Study participants who reported that family planning services at the facility were free of charge were 3.6 more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Those who reported that services were affordable were 4.28 more likely to get involved in postpartum family planning. Study participants who reported that services were always available were 8.41 more likely to participate in family planning. Study participants who reported a VHT as a family planning provider were 92% less likely to participate in family planning at 95% confidence interval.

Recommendations

The ministry of health should prioritize in facilitating sensitization campaigns through radio talk shows to further create awareness about male involvement in postpartum family planning.

At family level, couples are encouraged to discuss reproductive health issues including family planning among them such that they make informed decisions for the benefit of the family.

Kampala capital city authority in conjunction with ministry of health should derive mechanisms of ensuring that family planning services are always available at a free or affordable cost at all health facilities which will drive men to get involved in postpartum family planning.

At health facility level, family planning service providers should be well trained and knowledgeable health workers to offer services to clients so as to drive men to be involved in utilizing the services.

Acknowledgement

The authors do acknowledge the usual support of the academic staff of Faculty of Health Sciences towards the success of this study.

Authors’ Information

OK is a Medical Doctor and Lecturer in the Faculty of Health Sciences of Uganda Martyrs University. He is a senior researcher in the areas of Public Health, Health Services Management and Child focused research

MRM is a Public Health Practitioner with passion in Sexual Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR). Her goal in life is to advance women's empowerment and gender equality through research.

Declaration

The authors declare no conflict of interest and no external funding for this study

References

- Adera A, Belete T, Gebru A, Hagos A, Gebregziabher W (2015) Assessment of the role of men in family planning utilization at Edaga-Hamuse town, Tigray, North Ethiopia. Am J Nurs Sci 4: 174-181

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Adongo PB, Phillips JF, Kajihara B, Fayorsey C, Debpuur C, et al. (2018) Cultural eactors constraining the introduction of family planning among the Kassena-Nankana of Northern Ghana. Soc Sci Med 45:1789-1804

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Akafuah RA, Sossou MA (2008) Attitudes toward and use of knowledge about family planning among Ghanaian men. Int J Men's Health 7: 109–120

[Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- August F, Pembe AB, Mpembeni R, Axemo P, Darj E (2016) Community health workers can improve male involvement in maternal health: evidence from rural Tanzania. Glob Health Action 9:30064

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Balaiah D, Ghule M, Naik D, Parida R, Hazari K (2017) Fertility attitudes and family planning practices of men in a rural community of Maharashtra. J Fam Welf 47:56-67

- Basu S, Kapoor AK, Basu SK (2019) Knowledge, attitude and practice of family planning among tribals. J Fam Welf 50:24-30

- Bayray A (2012) Assessment of male involvement in family planning use among men in south eastern zone of Tigray, Ethiopia. J Med 2:1-10

- Bodin M, Kall L, Tyden T, Stern J, Drevin J, et al. (2017) Exploring men’s pregnancy-planning behaviour and fertility knowledge: a survey among fathers in Sweden. Ups J Med Sci 122:127-135

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Butto D, Mburu S (2015) Factors associated with male involvement in family planning in West Pokot County, Kenya. Univers J Public Health 3:160-168

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Cahill N, Sonneveldt E, Stover J, Weinberger M, Williamson J, et al. (2018) Modern contraceptive use, unmet need, and demand satisfied among women of reproductive age who are married or in a union in the focus countries of the Family Planning 2020 initiative: a systematic analysis using the Family Planning Estimation Tool. Lancet 391:870-882

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Chandra Mouli V, Camacho AV, Michaud PA (2013) WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. J Adolesc Health 52:517-522

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Chekole MK, Kahsay ZH, Medhanyie AA, Gebreslassie MA, Bezabh AM (2019) Husbands’ involvement in family planning use and its associated factors in pastoralist communities of Afar, Ethiopia. Reprod Health 16:1-7

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Davis J, Vyankandondera J, Luchters S, Simon D, Holmes W (2016) Male involvement in reproductive, maternal and child health: a qualitative study of policymaker and practitioner perspectives in the Pacific. Reproductive health 13:1-11

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Demissie DB, Kurke A, Awel A, Oljira K (2016) Male involvement in family planning and associated factors among Marriedin Malegedo town west Shoa zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Plan 15:11-18

[Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Demissie TW, Tegegne EM, Nigatu AM (2021) Involvement in family planning service utilization and associated factors among married men at Debre Tabor town, Northwest Ethiopia, 2017. Pan Afr Med J 38:211

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Dougherty A, Kayongo A, Deans S, Mundaka J, Nassali F, et al. (2018) Knowledge and use of family planning among men in rural Uganda. BMC Public Health 18:1-5

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Dral AA, Tolani MR, Smet E, Van Luijn A (2018) Factors influencing male involvement in family planning in Ntchisi district, Malawi–a qualitative study. Afr J Reprod Health 22:35-43

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Enyidah EIN, Enyidah NS, Eshemogie C (2020) Pattern of contraceptive use at a family planning clinic in Southern Nigeria. Int J Res Med Sci 8: 2082-2087

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Eqtait FA, Abushaikha L (2019) Male involvement in family planning: an integrative review. Open J Nurs 9:294-302

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

- Gopal P, Fisher D, Seruwagi G, Taddese HB (2020) Male involvement in reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health: evaluating gaps between policy and practice in Uganda. 17:114

[Crossref] [Googlescholar] [Indexed]

Open Access Journals

- Aquaculture & Veterinary Science

- Chemistry & Chemical Sciences

- Clinical Sciences

- Engineering

- General Science

- Genetics & Molecular Biology

- Health Care & Nursing

- Immunology & Microbiology

- Materials Science

- Mathematics & Physics

- Medical Sciences

- Neurology & Psychiatry

- Oncology & Cancer Science

- Pharmaceutical Sciences